2012 turned out to be a turning point for maturity in video-game storytelling. Games like Hotline Miami and The Walking Dead approached the age-old ultra-violence in video games debate with a certain empathy. If it wasn’t empathy, then it was pragmatism, and if it wasn’t pragmatism? Then it was disgust. The spectrum wavers between each insight made, yet despite this, there is still a philosophical conundrum with that.

How do you critique while participation is required? Is it right to sully a reward given, even when you know it’s wrong? It’s a tough barrier to break, and while it’s receded in recent years of more streamlined gaming experiences, this was a tricky tightrope to walk across. The inclination is that so long as you were rewarded for your efforts in the form of trophies or gamerscore, then your point would never have that impact.

Enter Spec Ops: The Line, the seminal third-person shooter released in June 2012 by Yager Entertainment, and a product as timeless as you could get in that time frame. Chronicling the questionable adventures of Captain John Walker and his squad, you’re sent to the aftermath of a sandstorm that ravaged Dubai, entrapping the civilians who survived within an impenetrable storm wall. When one rescue operation from an acclaimed U.S. Army battalion goes awry, Walker goes in, not just to amend the failed rescue, but to determine if a man he respects has survived.

"You Are Still A Good Person."

The nuances of Spec Ops: The Line are mostly well-known, talked to death in the past decade over heated debates regarding "ludonarrative dissonance." The contradictions that self-righteous narratives will have despite their usually-psychopathic tendencies are a dime a dozen, and from a distance, it’s fair to think the same of The Line. The game’s now-infamous scene involving white phosphorus could legitimately be seen as an abrupt tonal shift.

Still, that’s if you expect it to play out the same as other contemporary war shooters, which you shouldn’t, considering how the game approaches the ideology of your enemy. They’re fighting a losing battle against nature, considered godforsaken in a world moving without them, pretending that order is the answer when it all should’ve ended a long time ago. It’s not a tangled web of geopolitical cock-ups and escalating tensions between factions, but humanity doing what it does best: refusing to die, even when the odds are stacked against them, hands clawing for defiance.

A good example would be some of the contextual actions you can perform in-game, for immersion’s sake. If you’ve shot an enemy enough times, they won’t die outright; instead, they squirm on the floor for their final moments of life. While they’re downed, they’re no longer marked as an enemy, but you can still execute them. Granted, this is a violent affair, but it’s one that isn’t necessary. With that said, unless you’ve knocked them down with a melee attack beforehand, they won’t get back up, so you’re forced to consider whether prolonged suffering is better than the brutality you can inflict further.

Still, this doesn’t stop The Line from reaching a bit too far in certain areas of narrative involvement. The notion that “you could’ve stopped anytime” is poignant but briefly falters when you consider the game's theming. This isn’t a story solely about being the hero that the powers that be claim you will become, but the insanity that transpires from a games industry that’s able to relish in these worlds. As the game puts it, “To kill for yourself is murder. To kill for your government is heroic. To kill for entertainment is harmless.”

The juxtaposition of certain elements, like The Line’s horrifically unnecessary multiplayer component or the gamerscore given for committing a war crime, only helps to serve the game's point. The exhilaration that these games possessed, the wanton destruction you caused under the pretense of heroism, to promote this under any context of patriotism or otherwise was insanity. It never paints the player in a negative light, because how were you supposed to know? Instead, it just wants to let you know that you reap what you sow, and the video game outcomes you’re used to are not always how it plays out in real life. After all, we’re only human.

Cognitive Dissonance in the Industry

Did the video game industry specifically learn its lessons? Well, yes and no. The thing about contemporary war shooters was how they evolved between the dawn of Medal of Honor and The Line’s release and aftermath. What eventually started out as quaint war re-enactments of humanity’s victory following the fall of fascism grew into a perverse machine, churning out the same discrimination our ancestors fought against 80 years ago. Ironically, it would be Medal of Honor that would signal the end of this charade with the October 2012 release, Medal of Honor: Warfighter.

On a scale, if Spec Ops: The Line is held in the same breath as Come & See or Apocalypse Now, then Medal of Honor: Warfighter is Mel Gibson’s The Patriot. It is a glorified advert, so transparent in its promotion of the war machine, that it makes America’s Army look like Full Metal Jacket. Following two separate soldiers' attempts to stop an international terrorist plot, it’s an incoherent journey that seeks to paint its bloodthirsty characters as normal guys following orders, despite the neurotic enjoyment they gain from it.

Whereas The Line’s nuances sought to bring an undertone of affable humanity, corrupted by the “freedom” they attempt to bring to Dubai, Warfighter seeks to dehumanize its cast with no irony attached. Characters will warn you of “skinnies”, military slang used by American forces to describe African soldiers due to emaciation. Missions will have you armed with all of the U.S. military's might in order to take care of directionless insurgents. The mission “Shore Leave” has you decimating a building full of potential hostiles in a robot tank, before an unarmed civilian breaks the screen with a rock.

Bear in mind you’re rarely providing your own control in firefights, that commanding presence never showing through. You don’t even feel like a pawn most of the time, just a spectator to the revolving slideshow dedicated to showing off the toys of the U.S. Army. Even then, you’re surrounded by characters meant to be depicted as pragmatic arbiters of justice, when in reality, they’re more amoral sociopaths confusing evidence with confirmation bias.

To say that Warfighter was more than just a tone-deaf message of support for the troops is a crushing understatement. It was responsible for the temporary death of a franchise, the death of a studio, and also had seven Navy SEALs reprimanded after they leaked classified documents to Danger Close Games without seeking approval from their commanding officer. It’s a release that tainted not just a legacy, but stymied the progression of a sub-genre in and of itself.

There had to be a better field to graze than this, their escapist fantasies mutating in such a way that ultra-nationalistic values were seeping through. Is this the fault of developers and designers? No, absolutely not, it’s the committee overseeing these types of releases, from big-money publishers to the U.S. Army itself in more recent years. It’s the latter of which that’s of great importance, as with the recent release of Top Gun: Maverick, the idea of military recruitment adverts being more apparent in beloved media has shocked people, when it really shouldn’t.

For those who don’t know, if any movie you aspire to create requires materials and resources from the U.S. military-industrial complex for authenticity’s sake, then you no longer have creative control. The work will be looked over by military consultants and official Pentagon chiefs before it can be approved, and if there’s a niggling sense of uncertainty in how one portrays the U.S. military? Then they ask for certain elements to be modified or omitted outright, for fear of portraying the U.S. Army in a negative light. It should also be noted that this is covered even more extensively in the 2004 book Operation Hollywood: How the Pentagon Shapes and Censors the Movies by David L. Robb.

It’s a small but important piece of the puzzle when it comes to the fantasies that contemporary war shooters elevated into the spotlight by the seventh generation of gaming. It was no longer showcasing the work of special ops you’d never see in daily military life, like the adventures of Navy SEAL Richard Marcinko in Rogue Warrior or Criterion Games’ BLACK. This had become an out-and-out appropriation of culture, the lines beginning to blur between tropes and straight-up xenophobia, and you were going to be on the frontlines fighting it.

Needless to say, people caught on, and the story of Spec Ops: The Line was seen by the right people, who realized the direction these games were heading. The waters were starting to stagnate, and any titles that sought to showcase themselves in the same way were dismissed, both by the industry and its customers. Whether it was due to stale retreading of the same ideals or the questionable representations of the antagonist forces, the industry slowly moved on.

Feeling Like a Hero

From there, two paths were forged. Games like Battlefield 4, while still presenting a truly banal story detailing how cool joining the army would be, instead focused more on the ever-growing love for multiplayer experiences. Single-player experiences would continue where The Line left off, like the nuanced exploration of Nazis always being bastards in Wolfenstein: The New Order, or the emphatic return of movement-based shooters with DOOM (2016).

Any game in the AAA circle that decided to return to the seventh generation’s passion for contemporary warfare would instead turn to the future or past. The two World Wars would be covered extensively by Battlefield 1 and Battlefield V, both games utilizing a “War Stories” framing device to showcase smaller efforts that grew during the war. Anything else that didn’t fit into a contemporary warfare setting would instead push new frontiers of futuristic combat (Titanfall, Destiny) or try and grab a slice of the burgeoning Battle Royale genre (Fortnite, PUBG).

Still, for a time, the industry was learning to move on, to greener and brighter pastures. New universes were being formed with old materials, and there was a reinvigorated wonder for co-operative activities. For a while, it looked like there was no longer a focus on promoting an incessantly evil war machine… at least, until Modern Warfare (2019) was released, at which point, the cycle began anew.

For every good-willed gesture made to ensure that the human cost of many of these pointless acts of bloodshed would be accounted for, Modern Warfare (2019) would shatter what was built. A mockery of its own legacy, which had once stood proud to make a statement on individual efforts made during these conflicts, was now set aside to sell these perfect killers who never get anything wrong. Once again, those sweeping waves of sociopathic tendencies are mistaken for pragmatism that wants to codify the righteous actions of these individuals.

There’s a notion that you can only “fight fire with fire” which is prominent throughout the campaign, reaching a fever pitch when you threaten a man’s wife and child to locate a shipment. Price says with no pause that “You gotta get dirty if you wanna keep the world clean,” one of those lines that seek to underline your actions as navigating what can only be described as a “moral minefield.” In truth, this minefield is marred by its isolation from a large part of human error.

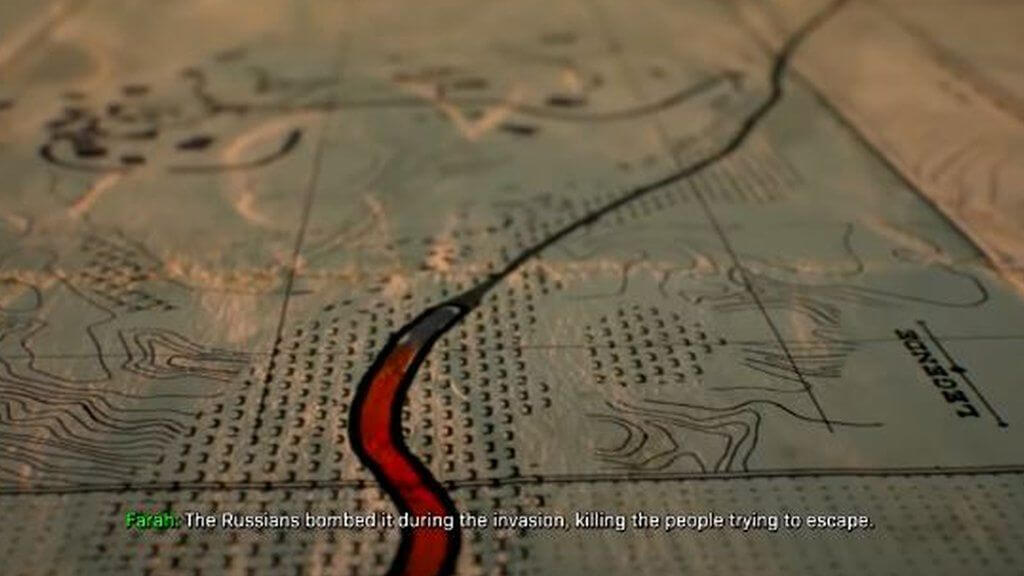

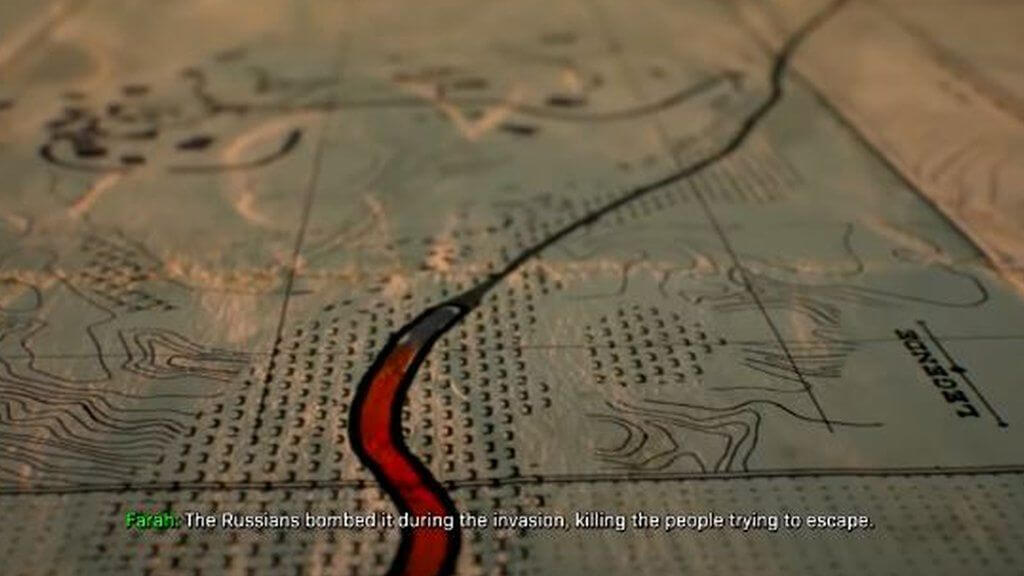

In fact, the only human part of Modern Warfare (2019) that resonates in any light is the story of Farah. The conflicts with her brother in regards to how they both want to protect their home country of the fictional, but nonetheless mutually relevant, Urzikstan are well-established grounds of debate. However, even this is marred by a militaristic need to redact, cover up, and modify events that correlate to real-life events, like the mentioning of the Highway of Death.

This is an actual stretch of road which leads from the Iraqi city of Basra into Kuwait City. In 1991, while 2,000 cars were preparing to enter the city, U.S. Army forces deadlocked the traffic from the front and back, laying waste to the entirety of the highway. It’s an attack that still has an unknown death toll, with a ballpark estimate being a minimum of 500 deaths. In the game, it’s attributed as a Russian attack in Urzikstan, which the Americans use to their benefit.

The logistics of the real Highway of Death incident are largely complicated, not only because of the horrific tragedy it was, but because of the context also. From the unknown death toll to the citizens and refugees being a part of the casualties, it’s an event from the Gulf War that the U.S. Army has vehemently defended -- most notably General Norman Schwarzkopf, the commander that led the attack -- as a righteous action that was necessary. At the same time, they’re completely fine with shifting the blame to Russians.

When it comes down to it, Modern Warfare (2019) is narratively unintelligent, setting forth a precedent that even its past statements meant nothing after a while. In truth, this was proven when a “tactical” nuke became a mainstay in multiplayer banter, a design choice that Fallout 76 imitated also with no irony attached. Anything else, like white phosphorus elevating itself from a heinous war crime to a reward you can use freely, is just the closing statement on a genre that has become a parody once more.

The Future of War Shooters

What does the future have in store for contemporary war shooters? Who’s to say. While Modern Warfare (2019) is able to shield itself from critique due to its superstar status in the gaming industry, other games attempting to promote the same ideals haven’t been so lucky. Six Days in Fallujah, a tragic retelling more than a decade in the making, has been lambasted every time it shows up, with Iraq War survivor Najla Bassim Abdulelah saying that she was "disgusted" by the inhumanity of retelling these events for profit, and people playing for fun.

Is there a point to these games? Largely, none of irreverent importance -- not anymore, at least. Medal of Honor: Warfighter will forever remain the series’ most impotent release, both mechanically and narratively. Modern Warfare (2019) will fly the multiplayer flag to kingdom come, given its single-player has forgotten its roots entirely, even for the sequel. As for Spec Ops: The Line? It can be credited for stifling the promotion of a war machine for a time. And as time proves? Lines fade.

hotline bling fortnite

hotline bling fortnite